Although some quilters were already venturing into modern patchwork back in the 1970s, our art would likely never have grown as widely without the appearance of one very practical object in the 1980s: the rotary cutter. This is a long and wonderful story, a success story just the way we like them, and it all began in Japan.

It’s hard to grasp what Japan looked like after World War II—after two nuclear bombs and widespread devastation. A proud people humiliated, entire cities leveled…

Let’s go to Osaka, the country’s second largest city after Tokyo, about 330 km (200 miles) from Hiroshima. Like so many others, Osaka was heavily bombed between March 13 and August 14, 1945, resulting in 10,000 civilian deaths. Among the survivors was the Okada family.

You know how it is—sometimes beautiful stories rise from the darkest places. Shortly after the armistice, American soldiers were still present, and the young Yoshio Okada was given a chocolate bar. It snapped cleanly into pieces with a simple twist—no effort, no tool. It was an unfamiliar flavor in traditional Japanese food. Did Yoshio, born in 1931, enjoy it? Who knows—but he remembered how easily it broke apart, how something hard could be divided with precision just by refining the material.

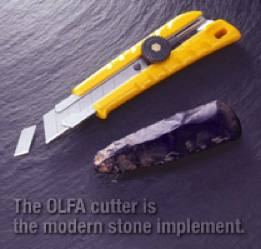

Yoshio’s family worked in printing. He became familiar with paper handling and got a job in the industry in the early 1950s. His job was cutting paper all day with razor blades—dangerous four-pointed blades that dulled quickly and could easily cut you. Yoshio first tried to improve their use by attaching a handle… then remembered the chocolate bar, and the shoemakers who used broken glass to shape soles, snapping it again and again to get a new sharp edge. Combining all of that, he created—after many trials—the world’s first snap-off blade cutter:

He and his brother tried to market the revolutionary idea, but no company wanted to invest a single yen. So, with all his savings, Yoshio made 3,000 units. They sold fast—they worked so well! But each one was handmade, with no uniformity. Standardization was needed.

Ergonomics was as important as efficiency. Yoshio tested hundreds of river stones to find the best hand fit. He also defined the perfect cutting angle (59°), the best blade alloy… All current standards—9 mm and 18 mm blades, and the iconic yellow color (to stand out in a dark toolbox)—come from Yoshio Okada and his ten years of development.

His company was originally called OKADA & Co., but after disagreements with investors and family, it became OLFA in 1969. “Ol-ha” means “to snap a blade” in Japanese, though the “h” is often dropped in other languages—so Ol-Fa it was! By 1971, these cutters started breaking into the U.S. market, and then globally. While Japan had a reputation for copying at the time, here it was setting the standard.

Eventually, patents expired, and competitors copied the design. Stanley (USA) became the other major name in snap-off cutters.

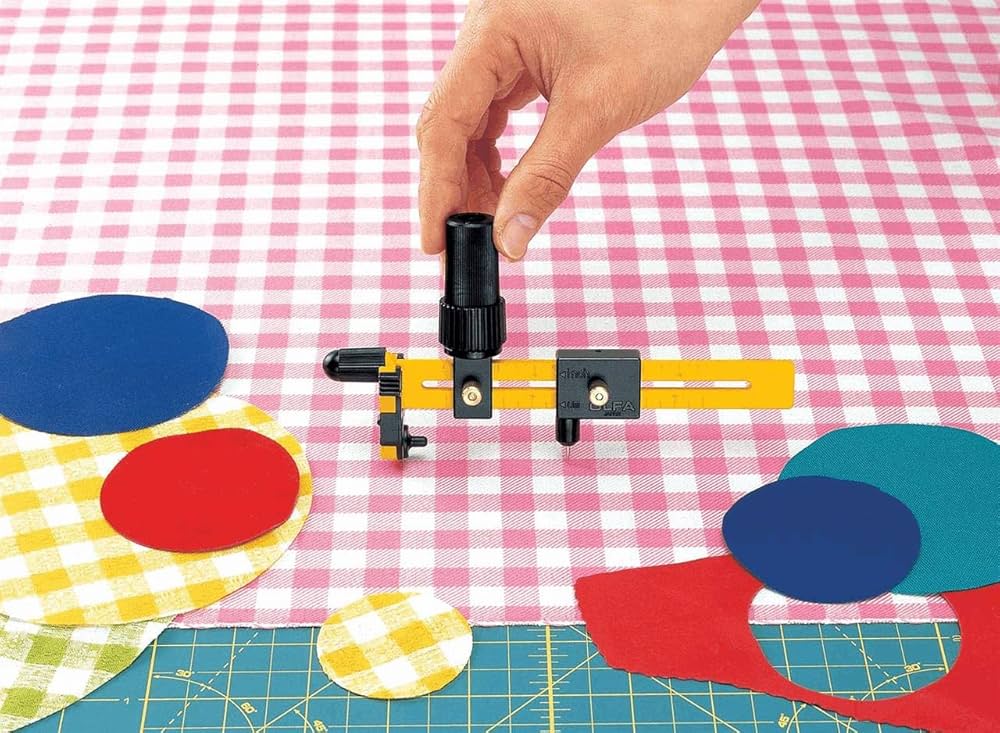

By 1979, success and wealth had arrived, but Mr. Okada’s inventive spirit was still alive. One evening, he watched a TV show where a seamstress struggled to cut fabric with oversized shears—awkward and inadequate. He mulled it over all night, and within days invented the solution:

This small cutting tool wouldn’t revolutionize fashion sewing… but it would change patchwork forever. It was Yoshio Okada’s final great invention. He passed away in 1990.

The yellow rotary cutter gained recognition, and in the early 2000s, Olfa redesigned it into collectible versions:

As rotary cutter patents expired, other brands appeared—Clover , Fiskars, and cheap knockoffs with much lower performance. It’s up to you to test and choose!

Competition spurred new designs:

The classic rotary cutter model sometimes makes blade changing tricky—you’re never quite sure where to place the little washer. Splash models address this with an easier blade change system and come in bright colors like turquoise and fuchsia, plus navy, lime green, purple…

Special editions occasionally appear—like this pale pink one supporting breast cancer research:

And then there’s the circular rotary cutter:

Today, Olfa is synonymous with high-performance cutting—used by workers, artists, crafters, and DIYers alike. The cutter is practical, efficient, and safe.

But how did the rotary cutter, invented by Yoshio Okada for seamstresses one night in 1979, become the signature tool of quilters in the 1980s? That’s another great story.

It leads us to YLI , a young company founded in Utah in 1979, aiming to supply high-quality thread for seamstresses, quilters, and the textile industry. Born at the end of the Peace & Love decade, the name Yarn Loft International seems to wink at the acronym ILY (I Love You)!

From the start, YLI had close ties with Japan—their flagship product was a cone thread for sergers, made in Japan. As the market evolved, they introduced many more products. They were the first to offer silk ribbon for embroidery. To this day, they continue sourcing silk threads and specialty cottons from Japan, serving both home sewists and industry professionals.

And it was through a YLI rep that the rotary cutter entered the U.S.—quietly. In 1980, a few of these odd-looking tools traveled alongside imported thread. The YLI representative handed some out during her tour—and Marti Michell received one.

I had the great pleasure of a long conversation with this leading lady of international patchwork in Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines in September 2014. With nostalgic charm and plenty of humor, she told me how one day, she revolutionized the world of quilting with a tool that looked like a pizza cutter!

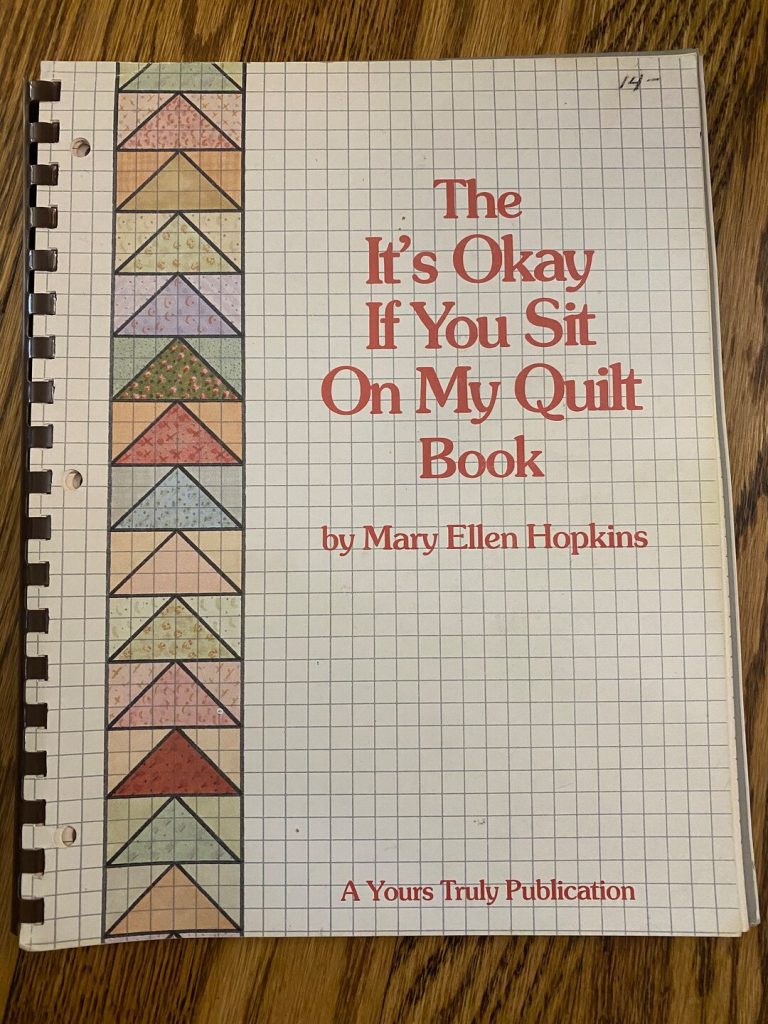

Marti grew up on a farm in Iowa, learning to sew from her mother. While studying journalism, she met her future husband. While raising their children, she also taught sewing and patchwork, with a growing sense that quilting wasn’t outdated at all—it was a beautiful way to reconnect with our grandmothers’ roots. Soon, the couple realized that people wanted fabric kits and patterns more than classes. Fabric stores were full of polyester and knits (like those used for t-shirts). So in 1972, they founded Yours Truly, working to reintroduce cotton by the yard and convincing suppliers to offer wide backing fabric. What’s common now was revolutionary then! They became well known nationwide as major suppliers of patchwork kits and, later, unbreakable plastic templates.

So in 1980, when the YLI rep gave Marti the strange pizza-wheel-shaped tool, she didn’t see the point and tucked it away in a drawer. But a few weeks later, her company was preparing the amusing and insightful book by Mary Ellen Hopkins, It’s Okay If You Sit on My Quilt. Mary Ellen wanted to feature a Seminole quilt, made of strips she didn’t want to tear. Back then, fabric strips for Log Cabins were often torn along the grain… it was another era!

Mary Ellen had custom acrylic bars made in various widths to mark cutting lines. One night, as Marti watched her work so painstakingly, a lightbulb went off. She pulled out the rotary cutter, protected her table, quickly cut through stacked fabrics… and the quilting world was never the same.

Cutting mats for DIY already existed, but Marti and Mary Ellen didn’t know that. It took a while before the trio rotary cutter, plexi ruler in inches, and cutting mat became standard. With Mary Ellen’s book in 1981—the first ever to mention the rotary cutter—the revolution was on. She was the first to teach how to use it, and soon many others developed new cutting and piecing techniques.

This revolution went beyond cutting: it changed measuring, too. Antique quilts often had tiny seam allowances to save fabric. In the 1970s, adding about 1/4 inch around templates became standard, but the sewn line still mattered most. Thanks to ultra-precise rotary cutting, you could now align fabric edges and stitch with a 1/4-inch presser foot—no need to mark seams. Everything changed!

First book explaining how to use the rotary cutter, 1981 (photo credit: Ebay)

Aligning the fabric edge with the right side of the 1/4-inch presser foot became the foundation of modern patchwork

The shift extended into the metric world too, with 1.5 cm added to each fabric piece (7 mm per side, plus a bit extra for the fold). Whether you use the imperial or metric system, inches or centimeters, what matters is consistency. The principle stays the same.

And that’s how the patchwork we know today was born—fast, precise, and joyful—thanks to a young man who once received a chocolate bar.

Behind this article :

Katell Renon

Katell Renon- Quilter, writer, teacher and curatorKatell Renon has been passionate about quilting since her teenage years. She first taught herself patchwork techniques before choosing to share her knowledge through workshops. She enjoys linking patchwork with general culture and women’s lives, which is why she regularly writes for specialized quilting magazines and on her blog La Ruche des Quilteuses .

She also curates collective exhibitions on original themes, such as the Weather Quilts (30 quilts exhibited at the 2021 Carrefour Quilt Show) or a textile interpretation of Lucinda Riley’s Seven Sisters saga (25 quilts and 9 textile books to be shown at the 2025 Carrefour Quilt Show).

She has authored two books on creativity and improvisation in modern patchwork. The second, Sacrés Tissus (2024), is still available.